Innovation across complex systems is incredibly hard and there are fewer places where it’s harder than on the frontline of the NHS. It’s a huge beast of an organisation, the 5th largest employer in the world, and with a budget of £127bn funded by taxpayers money the appetite for risk is low and accountability very high. There’s a unique, entrenched culture of public service and focus on frontline delivery which makes for an emotive sector and rightfully so.

In the face of this, Martin Ellis successfully led his team through a grand experiment in testing, iterating and scaling a unique new delivery model of outcomes-based commissioning. Called a Commissioner-Provider Alliance, it’s the holy grail of care because it’s one of the few, truly patient-centred models.

Local leaders have recognised the value already created by the initiative, which includes 62% fewer patients needing care packages for longer than six weeks after leaving hospital. The programme has been formalised into One Croydon, formally bringing together employees from across the Council, health and social care providers and the community and voluntary sector to broaden the remit and to see what else it can do.

You can see a real-life example of how the programme changed lives in Robert’s story.

I caught up with Martin to find out what we can all learn from innovating across complex systems.

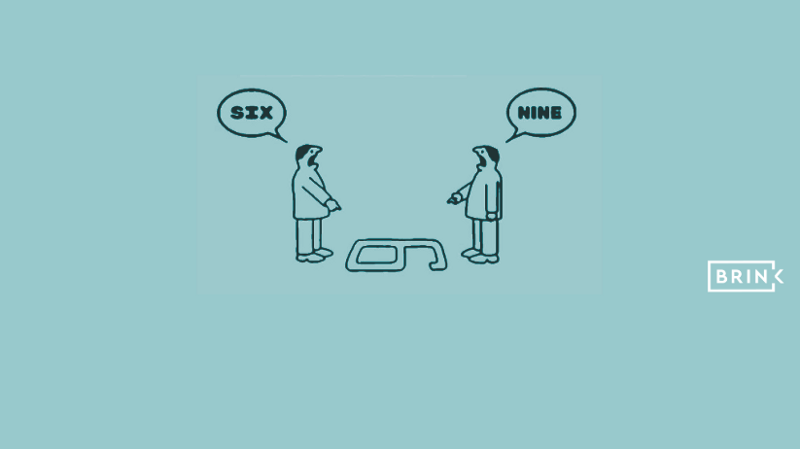

1. Giving everyone a view of the whole system changes the game

Before the experiment, all the commissioners and providers only knew their piece of the pie and were incentivised to grow their slice, not the whole pie.

“Bringing everyone together and giving all of us a unified view of the system showed us new opportunities. Together, we’re now able to respond to any challenge as a system”

As a result, people are talking to each other across organisations in a way that’s never been done before. Getting people to working outside organisational boundaries is hard and requires trust and incentives but the results make it worthwhile.

2. To incentivise trust, share the risk and reward amongst everyone

Once all partners realised the nub of their challenge was figuring out how all providers could collaborate, rather than compete, they understood they needed to nurture and reward trust. Each provider let go of some responsibility and removed organisational boundaries in a way that they’d never done before.

“The process of going through what behaviours we wanted, and understanding how each person felt certainly helped. Now, all partners are on board we have signed and delivered a £9m business case on a new model of care that’s unique to Croydon. We’ve been able to create a collective want to try this together.”

It took a multi-method approach:

• Of course, there was an element of building relationships which happened as much in the pub as in the boardroom.

• There were workshops on Org Design and on ways of working, which involved intentionally designing how to improve on relationships and take into consideration how everyone felt.

• And finally there was a focus on strengths. By identifying each organisation’s unique strengths, everyone in the system could play to those strengths.

NEXT PRACTICE: dismiss the myth of lone hero with payment structures that reward collaboration

Previously, all provider organisations were paid by activity so they were incentivised to work separately and achieve alone. By aligning incentives to all work together in an integrated way, the new model integrates health and social care provision around each patient and pays providers based on what they achieve as a group, not as individual players.

It is one of the few, truly patient-centred models and it relies on a progressive new way of budgeting (a capitated budget) which decouples payments from competing providers’ results and pays based on the patient’s outcomes instead.

The results are clear — GPs now speak to providers more directly than ever before and providers work to each others’ strengths rather than competing.

3. Deliberate velocity trumps mindless speed

By consciously focusing on a specific problem then delivering a portfolio of change targeted at that problem and allowing the time to see it through, the team were able to achieve so much more than with a scattergun or more organic approach.

“Purposeful innovation takes time and it’s slow and hard, but the results are worth it.”

Being an agent of change is a skill that takes cultivation and practice and whilst Martin trained formally via the likes of BT and University of Oxford, he also has a can-do attitude and curiosity around a problem which is necessary to hone for this kind of work. Certainly, it’s this mindset that allowed the team to weather the smaller experiments that failed along the way and ultimately led to the Alliance’s success.

4. Go there, accountably

Perhaps the greatest takeaway from Martin and the team’s work at the NHS is that they tried something, systematically. They came together with a shared appetite to try, and recognised that to do something new does not mean being reckless. By learning through experimentation, and iteration, Martin and the group were able to test and iterate on models and approaches until they reached the permutation that truly enabled patient-centred care, as it exists today.

This article is part of Brink’s blog series where I’ve invited myself in to interview business leaders at organisations where I wish everyone knew about what they do there to create an innovation-enabling culture.

#innovation #culture #systems #human-centred #NHS #Brink