This morning I had the great pleasure of speaking at the Capital Enterprise members’ event to explore the question ‘what do we mean by inclusive innovation, inclusive growth and an inclusive economy for London?’

In a panel discussion alongside Nesta’s Head of Inclusive Innovation, OneTech and Capital Enterprise’s Head of Strategy and London Borough of Islington’s Councillor for Inclusive Economy and Jobs, we talked about how London might stimulate inclusive growth and inclusive innovation, and what we might measure to know we’re making headway.

It inspired me to write this short summary of some of the points raised. This is a starting point for discussion. What do you think? I’d love to hear your views.

Measuring what matters

In tech startup parlance, the term ‘vanity metrics’ is used when we measure things like number of followers on social media or number of clicks and likes on a post. These are things that make us feel good but really tell us nothing about the success of a business. Better to look at cost of acquisition, retention, sales conversions and a whole host of other, more meaningful metrics.

The same goes for interventions tackling knotty challenges like how to improve inclusive innovation, or how to power inclusive economic growth. We have a tendency to look at how many people went through a programme, or how many we got to the start line.

If we only measured what matters, what would we be counting and what patterns would we uncover?

What policy or other interventions should be looking at is the impact they have on the most excluded people they are targeting, on the organisations in the system (business, local authorities, agencies, service providers, etc) and on the system itself. Too often, measures look at the individual when it’s actually the system we need to change.

Relying on ‘if you see it you can be it’, is not enough

When we talk about inclusive innovation and/or growth, the conversation often tends towards how do we get more of those excluded people to participate in entrepreneurship, join founding teams, and so on. There’s a view that if we can see it, we can be it. If we show enough diverse role models and success stories, then entrepreneurship can become available to anyone. And there’s an element of truth in that. I didn’t know being a female entrepreneur was a career choice available to me until I saw women like me, having entrepreneurial success.

But relying on showing success (or failure) stories and role models as the way to incentivise and encourage excluded people to participate in the growth economy is missing a huge, unavoidable, hurdle. There are significant defaults and biases at play which mean women and minority groups cannot access funding and opportunity in the same way majority groups can, regardless of how motivated they are. Remember:

- Just 1p in every £1 goes to female-founded venture teams. This, even when we know having a woman on the team results in 30% better returns on investment and there are 5x more applications in the pipeline from female-founded teams than get funded

- The total number of black, female professors in the UK is a shockingly poor 25, in total, due to biases and prejudice in academia

What if we focused on debiasing the system and removing the barriers and disincentives to excluded groups participating in innovation and growth?

If we’re relying on entrepreneurialism and on sectors like deep tech to power innovation and growth, we need a complete rethink of the systems that support and drive them, and we need to check our biases. If we’re not allowing women and minority groups to rise through the system and we’re not backing them with capital and access to opportunity then regardless of their level of motivation they cannot succeed.

I’ve been researching trends in the way we support and manage innovation, with Nesta. There are early-stage efforts to debias venture funding, and in an ideal world these principles could be expanded to things like promotion in academia, but we still have a huge way to go and until then, human prejudice and bias is getting in the way.

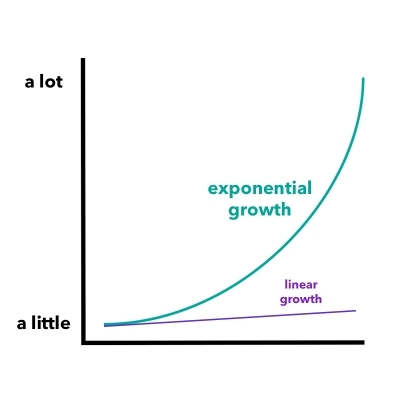

Getting to exponential upside

In the tech sector, and with venture-backed tech startups in particular, the quest is for exponential upside. This means that instead of linear growth, tech companies are on a quest for a sharp uptick in growth, a hockey-stick-shaped inflection point which typically follows an initial slow period of building, testing, iterating and learning. This idea of exponential growth, or adding a zero to each metric to get “10x” the growth is a well-known ambition in tech, popularised by the likes of Peter Thiel.

What if we applied this exponential upside thinking and methodology to inclusion policy?

What if we used the methods and processes so familiar to building tech startups, but on our inclusion strategies for innovation, growth and economy instead? By this I mean, starting small with a portfolio of experiments in policy interventions, testing, learning and iterating, then exiting what doesn’t work and scaling what does. I certainly do not mean running yet another pilot that doesn’t get to scale. Instead, how do we move away from the ‘pilotitis’, the fatigue of yet another pilot idea that doesn’t go anywhere, and focus instead on the crucial trinity of value (who will value this initiative / product / service), growth (what is the route to market and how will the idea move to sustainable scale?) and most importantly, impact (what effect will this have on the world, what size is that effect, and for whom?)

Holding everyone to account

During the discussion today, Nesta had a very useful approach to inclusive innovation that looks at who benefits, who participates, and who decides? I propose a build on that definition to add, who is responsible? What are our expectations of every part in the system and who are we holding to account?

What if we made inclusive innovation and growth the responsibility of everyone? What if we held all business, particularly the most productive and high growth businesses, to account against meaningful inclusion measures?

In London we have some of the world’s brightest minds, a world-class knowledge economy, and proven entrepreneurial talent able to spot problems and build solutions at scale. From Deliveroo to Deepmind. But business is not expected to really, truly bake inclusion into its ways of operating and growing.

What if we enlisted the knowledge and expertise available to tackle the inclusion problem? And what if we enrolled all businesses on the mission, and held them to account. It’s easy to consign challenges like inclusive growth to policy-makers but really it’s the responsibility of everyone. We already see this thinking in the likes of Imperial’s Ideas to Impact Challenge and MIT’s of the same name which closed its latest round yesterday, but I see a gap for London or UK-based challenges that’s not met, to my knowledge.

And it’s possible to measure business’ inclusion efforts against a rigorous benchmark and hold them to account. There are now some fantastic tools and measures like B Corp status, which track’s a company’s performance against a huge range of performance metrics including inclusion but crucially, expects those organisations to be profit-making, too. Brink is, I believe, one of the only B Corp-certified innovation practices but what if all innovation agencies were required to measure our inclusion and impact? The tools and are available and so, I believe, are the organisations that’d be keen to be involved. It’s up to policy-makers to enlist them.

I could go on, there are plenty more topics on my mind I’m not covering in detail here, like how do we create porous, truly inclusive innovation clusters (be it in a physical or digital space), how do we debias our datasets, and how do we instil innovative mindsets in the most excluded, and allow them the latitude (via funding) to experiment, fail, and eventually, succeed…but I’ll pause here for now.

I’d like to know, what does inclusive innovation mean to you and what is your role in enabling it?

What have I missed?