Local authorities need to build their innovation capacity as they develop new solutions to big challenges - here’s what I’ve learnt about how to make it happen.

Local authorities like city councils should be leading when it comes to innovating for the public good. They are democratic, place-based institutions that are very well placed to respond to local challenges and change people's lives for the better. And, because they are relatively more nimble and numerous than other forms of government, they can initiate forward-thinking policies that build towards regional, national, and global futures.

In practice, however, it's a lot messier. Local authorities are working with limited budgets and a political need to exhibit value for money in the short term. This contrasts with the notion that delivering solutions to complex problems requires new ideas that often “fail” in practice and which don’t provide immediate results.

I’ve seen first-hand the importance of local authorities, both as a citizen and through my work with Brink, which has been working predominantly with local authorities across Africa. I’ve found that these institutions are full of talented, committed people who want to build towards a better future and try new approaches.

But I’ve noticed a disheartening trend. Over recent decades and seemingly around the world, the authority of local authorities has diminished at exactly the time when they should be helping to respond to some of the great challenges of our time: environmental, economic, and social. Whether through budgetary cuts (austerity) following economic downturns, power struggles between local and national governments, a culture of outsourcing talent and decision-making power away from local authorities to consultancies and other privately accountable organisations, or a dominant approach to project management that’s focused on corporate-like targets and efficiencies, these developments have compromised the ability for local authorities to make bold decisions. It also discourages them from embracing uncertainty and from designing projects that act on evidence, adapt or pivot, and put learning (about their solution ideas, their users, and other stakeholders) at the heart of their agenda.

We are left in a sorry state where the physical city, as a sign of modernity and innovation, contrasts with the inability of its administration to react to changes within it and proactively build towards a future its citizens actually want.

Thankfully, a growing constellation of thought leaders is emerging on the topic of building skills for public sector innovation.

- Mazzucato and Anderson are introducing the idea of the public-sector capabilities index to “show us where local government capacity is strong, and where critical public-sector skills – such as public engagement through innovation, cross-sector collaboration, and leveraging data infrastructure and digital platforms – need to be strengthened.”

- Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics Action Lab is helping city authorities share and learn how to be a convener of diverse voices, steward of strategic plans, and the driver of change.

- Johanna Hoffman argues that we can use tools for imagination in the construction of speculative futures that give us new ways of thinking and designing for cities.

My own experience comes from ASToN, a pan-African digital transformation network based on the principles of peer learning and building the skills needed to implement digital transformation projects. It was inspired by an existing network methodology, URBACT, which is focused on Europe. Part of my role in ASToN was coaching cities to use innovation methodologies to experiment and use grant funding to develop their own digital solutions. One thing that was clear to me from this experience was the diversity of local authorities and the unique challenges they each face when it comes to innovating. For example, procurement practices, staff capacity, organisational culture, or various external factors can help or hinder the ability of local authorities to develop solutions.

Nevertheless, here are some learnings that I think are widely applicable:

1. An experimental approach is vital and can be applied in any bureaucracy.

Starting with the principles of lean experimentation can allow you to anchor around existing realities and ways of working instead of expecting something that might not be there. One of the tensions observed through ASToN was that, while you can have a team that is fully engaged in a method and with the openness to try new things, if a slow, procedural procurement system does not let them meet those ambitions, there is a limit to what might be possible. This made me wonder: do such disabling mechanisms act as unassailable barriers to experimentation? What I found was that you need to be realistic about what’s possible in the short term.

A significant part of coaching local authority teams focused on how experimentation principles could be put into action. For example, some cities were able to conduct rapid iterative cycles of product or service development, whereas for others, success meant simply encouraging a pilot phase before committing to the full rollout of a particular solution. The different orders of magnitude here show that across all cities, the principles of lean experimentation can be applied, albeit in a way that’s specific to their context.

2. A clearly articulated vision encourages curiosity and grounds future action.

Methodologies like lean experimentation embrace uncertainty, which can feel uncomfortable for practitioners to work with, especially when trying to use new frameworks and tools. I found that teams felt uncomfortable communicating this uncertainty to other stakeholders, which for me highlights a real need to express clarity and certitude, something that’s incentivised within many bureaucracies. Introducing new ways of working can also call into question the status quo, which does have an element of ego attached to it. These reflections highlight the very human need for teams to have psychological safety, which is the state of being confident that you won’t be judged or punished for being “wrong” or making mistakes.

We learned that a clearly articulated vision for the future can help a team feel safe because it allows local authorities to frame experimentation as a way to achieve impact. For example, Rehamna Province (Morocco) was designing a solution that would facilitate making health appointments across the territory. They used their vision for the future to host a meeting with doctors and health administrators, who were more than willing to join these engagements, help shape the solution, and even ask to be more involved in designing further iterations. Having an overarching vision supported the local authority in inviting stakeholders to collaborate towards achieving it. It also allowed the local authority not to eliminate the desire to be right or certain but to reframe their approach in a way that made space for co-design as a method to achieve their desired impact.

3. Peer-to-peer learning offers support and inspiration in equal measure.

One of the most exciting aspects of the ASToN project was its design as a pan-African network of local authorities, all undertaking the same journey. The local authorities we worked with were pioneers, often the first in their country's administration to work with certain methods, and were building digital tools with few to no regional precedents. For example, the City of Niamey (Niger) tested the digitisation of vehicle tax payments, which was the first digitisation of a tax initiative in the city. However, it also meant that city officials had to learn how to design, test, and roll out a digital solution from scratch.

The network approach allowed teams to share best practices, successes, and failures. It also led to personal and city-level linkages that continue past the lifespan of the project today. For local authorities like the City of Niamey, the connection, support, and fun of engaging with like-minded institutions helped their confidence grow as progress was made and allowed them to be inspired by others who had done similar things.

The importance of innovation mindsets

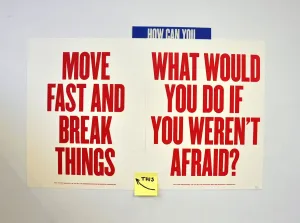

For me, one of the biggest truths when it comes to fostering innovation within local authorities is that it requires a sense of humility and openness to uncertainty. Plans can be reflected on, iterated, pivoted to something different, and sometimes completely abandoned. In an environment where “failure” might not be embraced in the same way as in Silicon Valley, this is a massive ask on public sector workers who are used to existing institutional norms that incentivise certitude and value for money. I was grateful to every local authority for their enthusiasm for their project, which has sometimes brought out these inherent tensions.

My key recommendation for those looking at public sector innovation is to appreciate not just the tools and methods that public institutions can deploy but also the existing organisational structures and incentives their human practitioners operate within and often become pioneers in spite of. It’s these practicalities of innovating within bureaucracies that are an exciting, growing area of understanding.

The story of the ASToN network is one of mutual learning of the methods, mechanisms, and mindsets needed to effectively encourage local authority teams to innovate and co-design bold solutions with citizens at the heart. The work is challenging, but through coaching, the support of independent experts, and collective learning– the core principle of the ASToN network–I believe we gave local authorities the best opportunity to develop and advocate for what’s needed.

Local authorities can build new capacities to help them navigate uncertainty and design solutions that work locally, both for and with their citizens, to make dents locally. I’m very excited about what the future holds for local authorities as they grow and develop, and I’m interested in collaborating with others working on local government innovation.

If that’s you, please reach out!

Read more on this topic in our case study: A city problem, not a citizen problem